Arabic Collections Online, a project in collaboration with the library at New York University Abu Dhabi, has won a $500,000 (Dh1.8 million) grant, reflecting the surprise reach of its impact beyond academia.

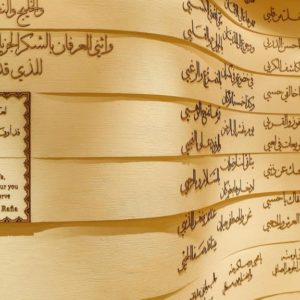

Arabic Collections Online began in 2010 with a simple idea: to take Arabic-language books that are out of copyright, scan them, and make them available to anyone who might be interested. NYUAD partnered with several leading universities – the main NYU campus in New York, Columbia, Cornell, Princeton, the American University of Beirut and the American University in Cairo – to identify public-domain books in their collections, and then put them online. The target is to have digitised 20,000 to 25,000 books by 2021, says Ginny Danielson, the outgoing head of the NYUAD library. They are currently at around 8,750.

As the project has progressed, however, its nature has changed. “Our expected audience was users in other universities, and we thought it would be useful for NYUAD,” says Danielson. “But where our usership has really taken off has been all over the Arabic-speaking Middle East.”

Access imperative

Danielson explains that users of the site first concentrated in Egypt, Lebanon and Morocco, which are traditional sites of the Arabic book publishing industry. “Then, when we started looking, we started seeing Algeria, and then a consistent top ten user base in Turkey, Iraq, Jordan, Syria. We realised that this database was providing reading materials for refugees.”

Contacts in publishing and libraries, such as the librarian at the University of Mosul, confirmed this suspicion: “People were trying to educate their children, create schools, and constitute libraries that had been bombed out of existence.”

While many digitisation projects focus on using technology to preserve rare books and manuscripts, it became quite clear that this project was, as Danielson says, “not a preservation imperative but an access imperative.”

Other usership statistics identify different pockets, and map out a landscape of readers starved for material: “We are seeing use in areas where there is a need for books,” says Danielson, simply. “There is readership outside the main cities. In Egypt, it wasn’t just Cairo but smaller towns – sometimes a university town, but sometimes just a small place where there wouldn’t necessarily be a bookstore.”

‘Libraries think in terms of the next 500 years’

The site has also been highly popular in the Gulf, where it can be difficult to get access to books published before 1950. The collection’s earliest books are from the 1850s – any manuscripts from earlier than that are generally too fragile to scan, and are usually kept in the rare books department of the library. In a pairing with the National Archives of the UAE, they’ve recently scanned an important 19th-century Arabic dictionary compiled by the Lebanese scholar Butrus al-Bustani. The other books are mostly novels or works from the social sciences – something that also accounts for the project’s accessibility.

“Scholars who published on the sciences or math tended to publish in European languages,” says Danielson. “When you go to an old library like Princeton or AUB and you pull out the Arabic books, you’re not going to get a 1930s biology textbook, you’re going to get a 1930s novel, or something from history or the social sciences – something that people in this day and age are interested in reading.”

The increased interest meant that Arabic Collections Online began looking for external funding, and last month announced that they had received $500,000 from the Carnegie Corporation in New York, who have supported other digitisation projects. The grant will help NYU combat a new problem in the millennia-long history of library collections: digital obsolescence.

As a quick scan of your own school days might suggest – who remembers microfiche? Floppy disk? CD-ROMs? – digitisation efforts are well and good, until your computer fails to recognise the file format.

“Libraries think in terms of the next 500 years,” says Danielson. “It’s not just slap it on a scanner and keep it on a server. Our systems are set up to record enough structural metadata about the scan that it can be stored in perpetuity: it can identify when the file format will become obsolete, and migrate it forward.”

Investing in academic technology

One of the ancillary benefits of such a large-scale project is that it brings best-practice library digitisation techniques to the UAE, with the metadata that can facilitate the often costly process of file migration, as well as “checksums”, embedded data that can detect whether any code from the stored file is deteriorating or missing.

The project complements other digitisation initiatives, such as that of Dubai philanthropist Juma Al Majid, who has entered into agreements with various national libraries. Al Majid, who has a library complex in Deira, offers international libraries scanning equipment in return for access to the digital copies they create.

Digital technology has been a major focus of both NYU and the NYUAD library. Only 10 per cent of the books available in the NYUAD library are in hard copy; the remaining 90 per cent is digitally accessible. Perhaps more importantly, the library has begun collecting and disseminating hardware and software programs as if they were books, so that the likes of digital software for musical notation are housed in the central library rather than in a specific academic department.

“Academic technology is lodged in the library,” Danielson says. “NYU globally has invested more in academic technology than any other American institution.”

To access Arabic Collections Online, visit dlib.nyu.edu/aco

Source: The National, 24 July 2018